“History never repeats itself, but the Kaleidoscopic combinations of the

pictured present often seem constructed out of

the broken fragments of antique legends.”

From “The Gilded Age, a Tale of To-Day” by Mark Twain

and Charles Dudley Warner, American Publishing Company, 1874.

On September 6, 1901, President William McKinley was in Buffalo, New York for the Pan American Exposition as part of his re-election tour.

A man named Leon Czolgosz waited in a receiving line for the President and upon reaching the head of the line, Czolgosz shot the President twice with a revolver he had purchased four days before.

Two women became famous for their portraits of President McKinley shortly before he died. President McKinley sat for one of them, Lillian Thomas, a talented painter, born in Cleveland, Ohio and living in Washington, DC –

and Frances Benjamin Johnston, a well-known photographer, who was at the Pan American Exposition and took photos of President McKinley within hours of his being shot.

The Frances Benjamin Johnston’s photograph collection at the Library of Congress includes a Thomas Marceau photo of Lillian Thomas.

McKinley died on September 14, 1901 and McKinley’s Vice President, Theodore Roosevelt, became President.

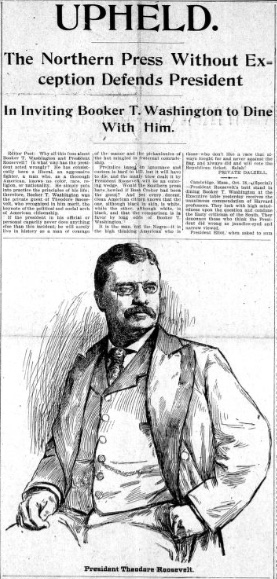

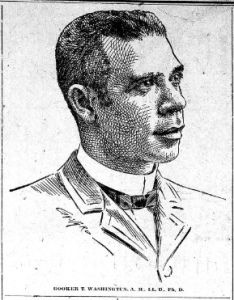

In October 1901, United States President Theodore Roosevelt invited Tuskeegee Institute President Booker T. Washington to the White House for dinner along with Philip B. Stewart.

The dinner was a significant event and applauded by many.

Theodore Roosevelt, like William McKinley before him, often conferred with Booker T. Washington about race, political and education topics. As president and founder of the Tuskeegee Institute, Washington was well-regarded around the country.

Despite Washington’s accomplishments, some, particularly those from the southern United States, accused the President of degrading the office by inviting him.

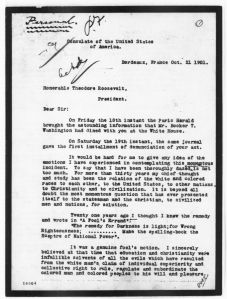

Of those letters in support of President Roosevelt’s decision to invite Booker T. Washington, one deserves particular mention – that from Abion W. Tourgee to President Roosevelt.

Albion Tourgee was an attorney for Homer Plessy in the tragic 1896 case, Plessy v. Ferguson which sent equal treatment under the law in the United States tumbling backwards, setting a legal precedent that was not overturned until almost 60 years later by Brown v. the Board of Education in 1954.

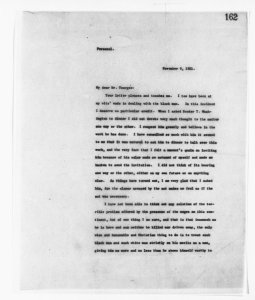

In Tourgee’s letter to Roosevelt, he expressed hopes for the country and praised Roosevelt for his actions. Roosevelt, on the other hand, revealed to Tourgee that he hadn’t thought much about it and extended the invitation on impulse.

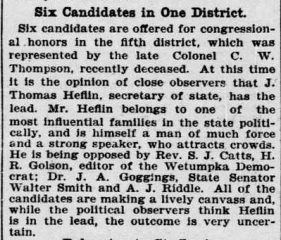

By 1904, Roosevelt was campaigning for re-election on his own behalf. While he campaigned, another man, James Thomas Heflin, was seeking election for a position he held as a result of the death of his predecessor, U.S. Representative Charles W. Thompson, of Alabama. Heflin represented the district in which the Tuskegee Institute was located. Booker T. Washington was his constituent.

Heflin was against women’s suffrage, but in favor of labor and states’s rights. He was against interracial marriage and helped draft the Alabama state constitution which included language disfranchising African Americans from the right to vote.

While on the campaign trail, Heflin made statements suggesting that it would not have been a bad thing if Roosevelt and Washington had been blown up by someone like Czolgosz.

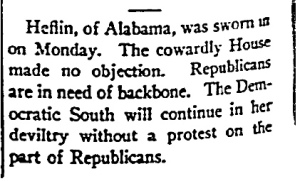

Although Heflin’s comments were generally condemned, there were no repercussions for his statements and convinced officials and the public that he was making a joke. He won re-election.

Upon Heflin’s re-election, he introduced several bills intending to harm federal elections, encourage Jim Crow cars, and bills to reduce competition in cotton futures trading.

To that end, he introduced legislation to establish Jim Crow cars in the Maryland and the District of Columbia. He falsely claimed that many African Americans in the District of Columbia supported such a measure.

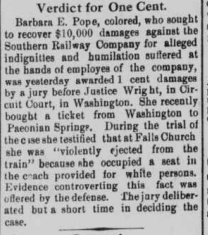

At least three people responded to the Evening Star reports by Heflin. Those people were E.M. Hewlett, M. Grant Lucas and Barbara E. Pope, an educator and author who later became a member of the Niagara Movement and brought her own Jim Crow case in Virginia shortly before the 2nd Niagara Movement’s meeting Harper’s Ferry.

President Roosevelt’s sentiment set forth in his letter to Tourgee, was belied by his actions in 1906, when he summarily discharged, without honor and without an opportunity to defend themselves, the entire regiment of 167 men in Brownsville, Texas. These soldiers were prevented from serving in the military and resulted in the denial of several pensions for those who had served more than 20 years.

Roosevelt’s announcement appeared to be timed to be made after the 1906 election.

. Washington, 1906. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.24001000/

This incident, which occurred the same week as the 2nd Niagara Movement Meeting in Harper’s Ferry, WV (August 15-18, 1906) – the 1st being held in Buffalo, NY in 1905, was indicative of rising tensions in the country, increased voting rights disfranchisement for African Americans, and epidemic level lynching numbers. Despite criticism, Roosevelt did not publicly apologize for his decision.

It was not until the Nixon Administration in 1972, after decades of investigation, when Congress determined the soldiers were innocent. Nixon pardoned the solders and granted them honorable discharges, yet none of the surviving soldiers were given backpay, although some financial restitution was paid.

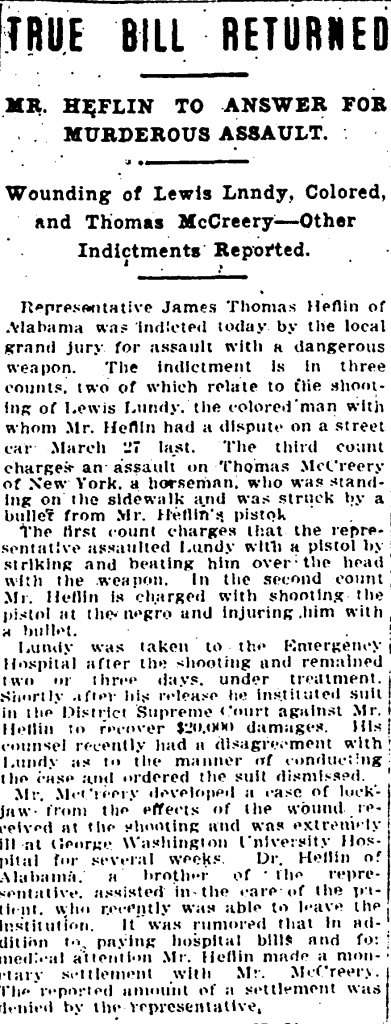

By 1908, Heflin was well-known for his support of the “lost cause” and spoke at related events. In April 1908, upon the pretense of defending a white woman on a DC railcar on which he was riding, he forced an African American man, Louis Lundy, from the railcar and shot at him through a railcar window, hitting him and an innocent bystander, Thomas McCreery, both of whom were injured.

Heflin’s family came to the aid of McCreery, the white man who was injured. Heflin’s brother, Dr. Heflin went to great lengths to assist him. Louis Lundy, the target of Heflin’s rage, received no special care.

Ultimately, Heflin was indicted, but the charges were later dismissed.

By early 1908, Heflin’s attempt to force Jim Crow laws on the District of Columbia by amendment was defeated.

Barbara Pope’s Jim Crow case was successful, although the jury awarded her only one cent in damages.

These incidents were mere bumps in Heflin’s decades long career. None of these transgressions impacted Heflin’s election prospects. When Woodrow Wilson was President, Heflin introduced legislation resulting in national recognition of Mother’s Day in 1914. He remained in the United States Congress until he was barred from participating in a U.S. Senate campaign in 1930.

African Americans continued to attend meetings in the White House, but were not invited to social events until the wife of Congressman Oscar Stanton De Priest of Chicago, Jessie Williams De Priest, was invited to a tea scheduled for June 12, 1929 by Louise Henry Hoover, President Herbert Hoover’s wife. Congressman DePriest was the first African American elected to Congress not from a southern state. When he was elected in 1928, he was the first African American elected to Congress in the twentieth century.

Mrs. Hoover was careful to ensure that the tea would be comfortable for Mrs. DePriest and the other guests. The invitation list was prepared in secret and it wasn’t until after the tea was held that the public was aware of the event.

The DePriests and The Hoovers received hostile responses because of The Tea. Many Americans remained of the belief that social interaction between those separated only by skin color, suggested that such interaction signaled social equality.

Congressman DePriest served from 1929-1935 and departed from Washington, DC when he was not re-elected. The DePriests returned to Chicago.